Published 28th Apr, 2019

In his award-winning book, The Big Short, author Michael Lewis chronicles the journey of Michael Burry, a physician turned hedge fund manager who bets big against the Real Estate Market and wins. This is a man who is so sure of his bet that he prods banks to create complex financial instruments just so that he could short the subprime mortgage market directly. I remember reading the book and being fascinated by the idea of taking such a bet. Unlike betting on growth stories, shorting involves making money on the back of failures. Profiteering off of somebody else’ misery might not immediately sound compelling. But it does facilitate a larger purpose — of extracting the true value of an asset. Short sellers help achieve this by aggressively selling overvalued stocks.

The theoretical mechanics of short selling is rather simple. You borrow a certain number of shares of a company from your friendly neighbourhood broker and you sell these shares at the current market price — say Rs.100. At some point in the future when the stock price dips (to Rs.80), you buy the company shares from the open market and return it to the friendly neighbourhood broker. The transaction is settled and you make a decent profit. However, if the stock price goes up in value, there is no real theoretical limit on the total amount of losses that you could potentially accrue. The reason why I repeatedly stress the word ‘theoretical’ is because in practice shorting doesn’t exactly work this way. However, the underlying principle still holds validity, in that you can make money by betting against the market and could potentially lose a whole lot in the process as well.

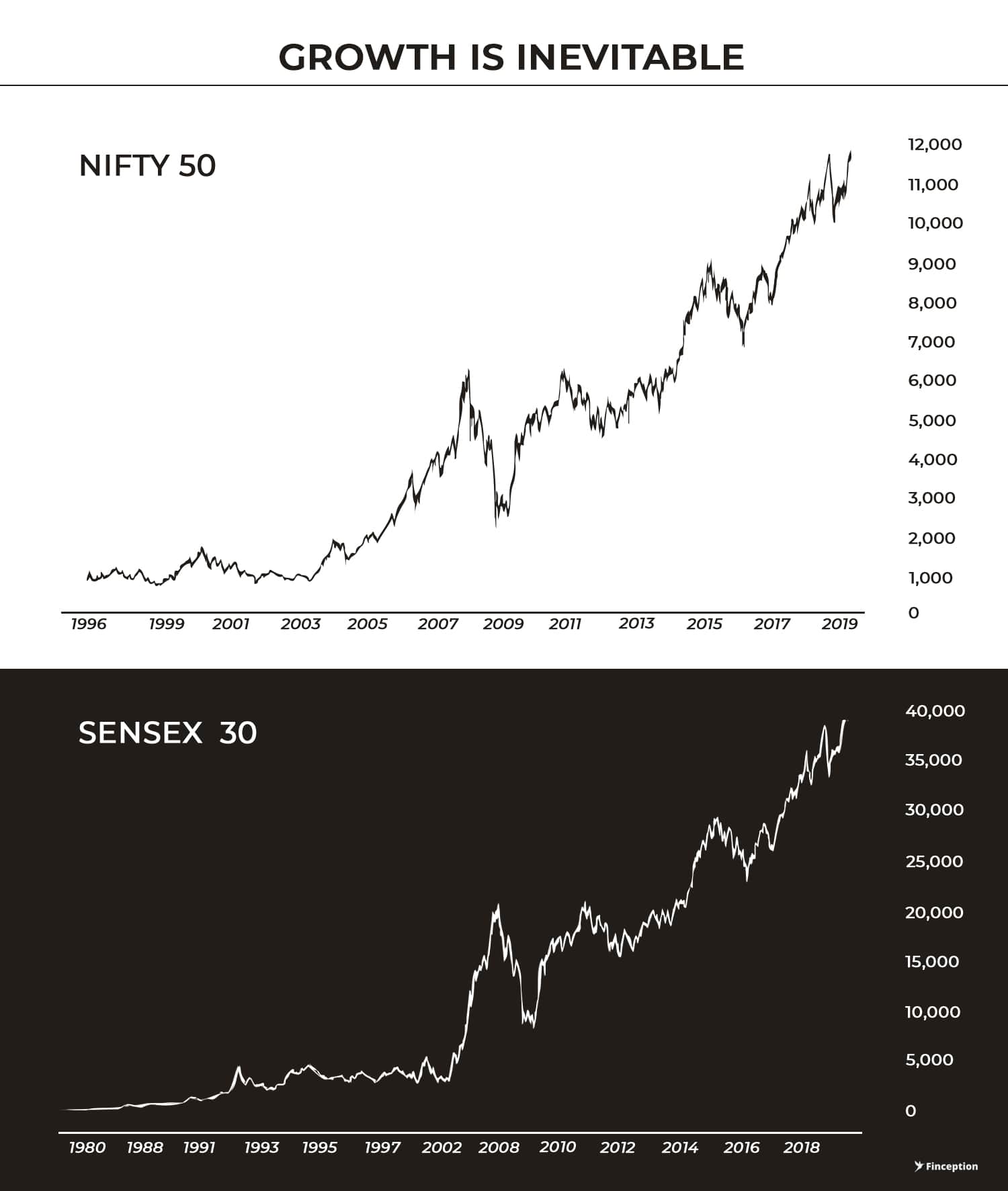

In fact, statistical odds simply aren't in your favour when you are betting against a random stock. Over the past 40 years, the Indian market i.e. the aggregate composition of all publicly listed companies has grown exponentially; which means a randomly selected stock is more likely to have done well than not. As such, shorting a random stock would have been a grave miscalculation. Even the best practitioners of the ‘Shorting School of Thought’are generally bullish on the market over the long run. While they might choose to short specific companies they almost always hold a portfolio that is dominated by stocks they think would rally upwards in the long run. However, despite the obvious shortcomings there is still merit in exploring the sacred art of betting on the downside.

Recently, we had the pleasure of meeting a renowned civil servant and talking to him for quite a bit about our journey here at Finception and investing in general. He was a keen observer and had done fairly well for himself on the back of some really good investments. He was kind enough to give us a sneak peek into some of his more recent bets and we were all ears. One idea, in particular, caught my attention. He was short on Just Dial. For the uninitiated, Just Dial sells listings to SME businesses in the country. If you are a paid customer Just Dial promises to bring in more leads and this is an enticing proposition so long as the business owner sees actual traction from the listing. JustDial also happens to be one of the very few publicly listed internet companies to be profitable. Unfortunately the gentleman we met thought otherwise.

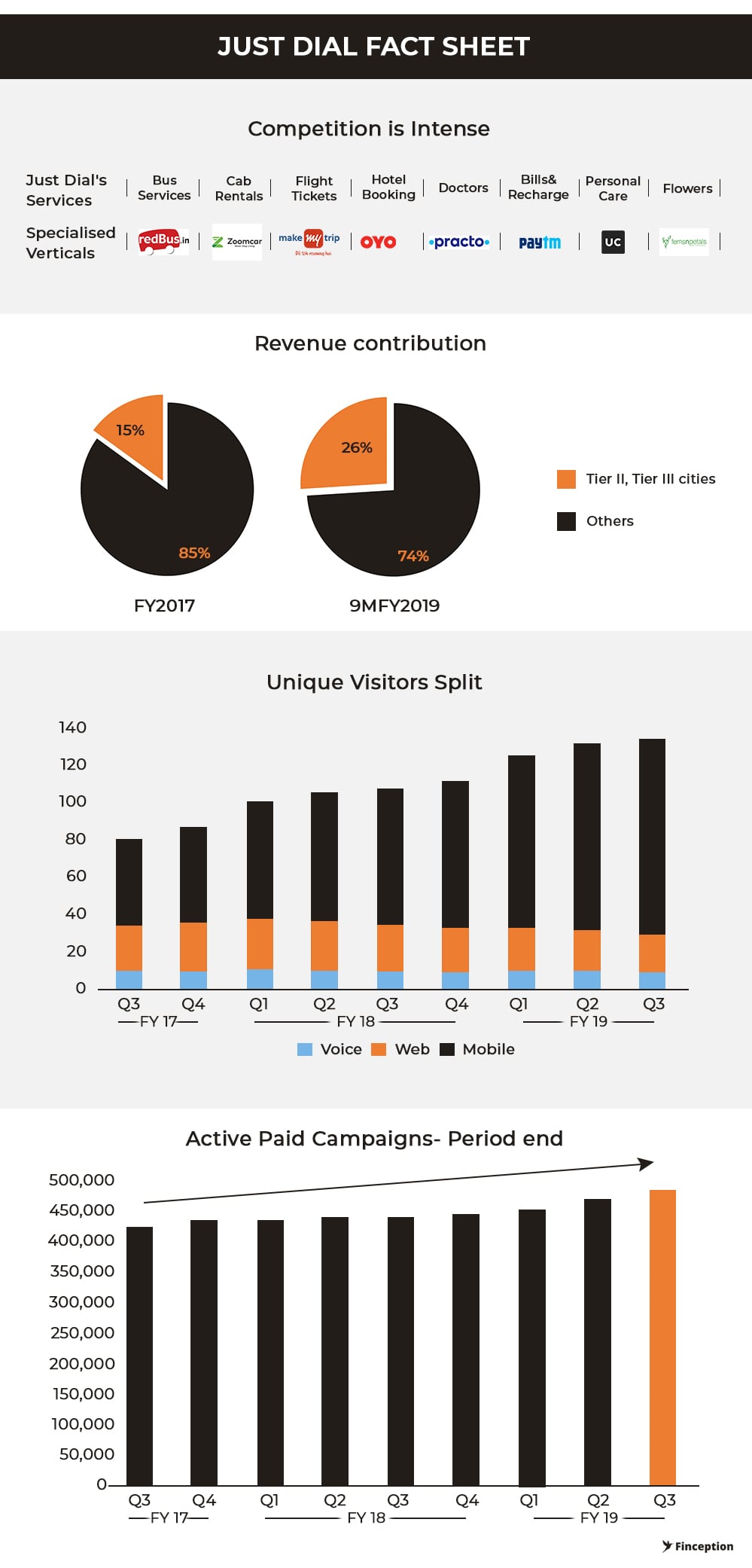

His thesis was this — As a business, Just Dial might still be doing well. But it’s doing well largely in part due to a burgeoning sales force that keeps prodding its customers to upgrade to paid services. These sales agents are the lifeblood of the company considering Just Dial loses over 40% of their active paid customers every year. Because of the high churn, maintaining growth is an unenviable task, a task that can only be made possible through an even larger workforce than it currently harbours. However, this equation presents a unique challenge. What happens when deploying an additional sales resource no longer yields the required growth. This ideally is the point of no return. Unless the company can diversify or add more value to its existing customers, a turnaround is unlikely to materialise. To its credit, Just Dial has been trying to do just that — add more value to its customers through extensions including Search Plus and JD Omni. Unfortunately, the reception has been far from spectacular. So Justdial went ahead and did the next best thing. It rationalised its cost structure and returned to its core focus — SME listing, only this time they are targeting the Tier II, Tier III SMEs.

The second half of the argument is that such an endeavour is futile. In smaller cities, SMEs don’t need to advertise as much because it’s not really that hard to find a local tailor/carpenter. People in these areas are already well aware of most local businesses and so it’s not a lucrative opportunity for the SME promoter to pay 20,000 for a paid listing. So the Tier II, Tier III city gambit might not work as well. Larger cities pose their own set of problems. Search is now highly specialised along specific verticals. If you need a doctor, you don’t go to Just Dial anymore. Instead, you visit Practo, a service specialising in connecting you to your next door physician. If you need a taxi you go to Uber. So there’s considerable competitive pressure there. If you were to tie in all these elements and create a larger narrative, that narrative is likely to centre on how JustDial is running out of options to keep sustaining its growth.

Now we are not saying that this in itself is a watertight thesis. But if one were to venture into the “short” side, they would probably need to work out a thesis very similar to the one the gentleman presented. Focus on the business, exhaust most possibilities and then draw a roadmap of where the company is headed. Unfortunately, there is just one problem. Just Dial isn't anywhere close to this doomsday scenario yet. It’s seeing healthy sales growth and the “point of no return” that we earlier hypothesised could happen anytime over the next 5 years (based on our own internal calculations). One might even argue that it might never happen at all. Considering the nature of internet businesses there is still a chance (albeit very tiny) that Justdial might, in fact, wriggle out of this quagmire relatively unscathed. And even if it doesn’t it still has a strong foothold in the SME listings market. The stock price might see some downside but it’s most definitely not walking to the graveyard.

This is perhaps where two rules adopted by one of shorting’s most famous practitioner comes in handy. The idea is pretty simple. You never pick stocks that are going to dip just a wee little in the short term and try to profiteer off of such trades. Instead, you pick genuine failures — stocks that are destined to go to zero. Meanwhile, you take up your position only after the downward swing has already commenced. Meaning the downward momentum ought to be so strong that the possibility of there ever being a rebound is close to zero.

This was a position we took on Jet Airways almost a year ago. We did this not because we possessed some unique insight into the industry dynamics that nobody else had. Instead, we did it by posing a series of questions that led us to believe there were only one of two possible outcomes. A merger/bailout or bankruptcy. Before we get into our line of reasoning it’s imperative we understand a very important airline metric — Available Seat Kilometres. Imagine Jet operated a single flight with 100 seats and the flight travels a total distance of 100 kilometres. The total available seat kilometres is 10,000. Because jet operates multiple flights with different seat configurations, you add up all the flights and the total distance each flight travels and you get the total available seat kilometres. Available seat kilometres is indicative of the total capacity and Jet was losing money on every available seat kilometre.

They pinned the blame on oil prices. They were right. Oil prices were firming up and fuel is, in fact, a significant component of the cost structure [measured using another esoteric metric — Cost per available seat kilometre (CASK)]. This meant they had very little control over their expenses, although they never admitted this much. Their non-fuel CASK (maintenance etc.) did show signs of improvement. However, it wasn’t enough to compensate for the losses. Meanwhile, their RASK (Revenue per available seat kilometre) remained flat. This was due to the advent of low-cost airlines and their refusal to hike prices.

So considering Jet was making a loss on every seat they flew, a prudent investor would think that it would make sense to stop adding further capacity until they could figure out how to turn a small profit on each passenger they flew. However Jet continued to expand its fleet size and fly to more destinations. This might seem counterintuitive, however, it’s not really that hard to understand why Jet would resort to such a measure. Jet had been ceding market share to low-cost airlines for quite some time and if it were to ever breach a minimum threshold it would become virtually impossible to keep its planes flying because of the fixed costs the company incurs every year.

So here we had a company that couldn’t afford to lose any more market share but kept losing money the more it flew. The only other recourse available to Jet was if somehow it could convince the collective conscience of the airline industry to start raising ticket prices. However, barring divine intervention, such a scenario seemed entirely implausible the way low-cost airlines had positioned themselves. So with cash quickly running out, we had exhausted every exit option available and we knew Jet was going down the route of Kingfisher.

So did we short it? No, we didn’t. Even if we did we would have bailed soon after. Jet’s stock price swung wildly even at the slightest rumour. An experience like that would cripple us, even if there was considerable downward momentum. It’s quite easy for us to make this hypothesis and write an article about it in the comfort of our cubicles but to truly suffer through the gyrations of the market is a whole different matter altogether. Granted that stock price movements are not unique to shorting. Even people betting on the long term have to live through the same dynamics. However, there are slight differences. For one, anytime the stock moves up, you need to have additional capital buffers to cover your position. Second, people are generally optimists and as optimism grips the collective conscience of the investing community the upside swings appear more pronounced than their downward counterparts. Even rotten stocks can hobble around for quite some time before they actually kick the bucket. Shorting isn’t for the weak hearted. In fact, if it weren’t for an academic curiosity we would never even be writing this piece. The only takeaway here is that if you were to be so brave that you still want to short stocks, build a watertight hypothesis and pray that the stock goes to zero.

. . .

Enjoyed reading? Show us your love by sharing...

Tweet this articleReview & Analysis by Pawan, IIM Ahmedabad

Liked what you just read? Get all our articles delivered straight to you.

Subscribe to our alertsREAD NEXT

Get our latest content delivered straight to your inbox or WhatsApp or Telegram!

Subscribe to our alerts