"If you want to be a Millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline"

On 10th August 2018, the chairman of Jet Airways Naresh Goyal offered a public apology to the company's shareholders. He did not have much to say except that he was sorry people lost wealth on account of Jet's poor performance in the recent past. "I feel guilty and embarrassed" were the words that echoed throughout the investor community. By all accounts, this is a terrible state of affairs. No promoter should have to go to through this and no shareholder should have to see his wealth erode so precipitously in the markets. But the Airline Industry is almost unique in this regard, in that it has consistently managed to throw curveballs time and again to both investors and promoters alike.

So today instead of looking at complicated operational metrics and financial performance of airline companies, we will do something different. We will instead look at air travel and why flying is a terrible experience. Why we have great fund managers [Buffett, Lynch] hating on the airline industry and how all of this is connected to airfares in general and through it, you, fellow investor.

. . .

Let me preface this story by stating explicitly that I have strong opinions about airfares and air travel in general. I think I am paying too much while being treated rather discourteously by the staff when I board most airlines in India. Consider flight cancellations. Often times flights are delayed/cancelled either due to technical snags in the aircraft or if the crew couldn't be ferried to the appropriate location on time. Airlines could radically minimize the frequency of disruptions if they built contingency plans i.e. keep extra aircraft or crew on standby. However, having a spare aircraft on standby is a lost opportunity to make money and in the aviation industry, this practice is shunned upon almost universally.

Overbooking is another menace that often ruins the flight experience. Airlines consistently overbook — meaning they book more passengers than the actual capacity of the flight in an attempt to maximize their profit-making potential. They do this by accounting for the total number of passengers who are unlikely to show up. This policy of overbooking is also premised on the same idea — A sold seat that remains empty is an opportunity lost and airlines make every attempt to fill the plane. But in the process of overbooking, customers often get bumped out of flights that they legally paid for. On average(monthly), around 2000 customers were denied boarding during the past 10 months and it seems airlines aren't really bothered about this disturbing trend. This brings us back to airfares in general

Despite my own personal opinion about prices, Indian airlines offer some of the cheapest flights you could find anywhere on the planet. The high prices that we think we pay for flights are in reality dirt cheap considering global standards and this means airlines run on very thin margins. Eliminating overbooking as a policy or operating spare crew and aircraft would almost inevitably translate to higher fares and its a price that Indian consumers have refused to pay for. In return, low-cost airlines have obliged by cutting fares and pairing it with sub-par customer experience. On the opposite spectrum, airlines that have attempted to offer a more high-end refined experience [Kingfisher] have consistently failed to make profits in the face of intense competition. The bottom line here is that the economics of running an airline is a whole different ballgame and working out a profitable business model often leads to an unpleasant experience for most patrons

As the popular digital news magazine Vox notes — "A pleasant airline to fly on would routinely have empty seats on its planes so nobody would have to get bumped and it would be easy to reschedule…[However], wherever competition has reared its head in the industry, the mass market has aimed for low prices above all else, followed by a vigorous culture of collective complaining when something goes wrong." So if the only way to make any real money is to go cheap, perhaps it pays to look at the pioneer of low cost flying in India — Indigo Airlines

The thing about Indigo Airlines is that the entire upstart was premised on offering rock-bottom prices to its patrons. It does this by keeping its costs low and running a tight ship. Take for example Indigo's fleet optimization strategy. Indigo flies to fewer destinations than Spicejet and Jet Airways despite operating a considerably larger fleet than its competitors. It flies to a mere 50 destinations (domestic) even after flying over 200 aeroplanes. Operating out of limited destinations means Indigo can afford to employ relatively fewer ground-staff, in turn, reducing costs. This is merely one of the many optimizations that the airline deploys to pursue profitability. Unfortunately, as we have already described most low-cost airline policies are not as benign, instead implemented at the expense of quality customer service.

On December 26th, Derek O'Brien, the chairman of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Tourism and Aviation launched a scathing attack on Indigo Airlines calling it the worst performing airline for consumers. The committee's grouse was in large part attributed to how Indigo behaves with its customers, charging patrons excessively for overweight baggage and the exorbitant pricing structure employed by most airlines during the festive season. According to Derek O'Brien, the committee also batted for cancellation charges to be capped at 50% of the basic fare and he finally topped it by saying — "Airlines are charging too much." This statement came against the backdrop of a financial quarter that saw Indigo making its biggest loss. It seems we have finally appeared at a crossroad. On the one hand, we have the standing committee claiming that airlines are overcharging customers and on the other hand, we have the most profitable airline in India making its first big loss. How do you resolve the conflict?

Every time an airline seems to make money, market dynamics disrupt the equation. If market dynamics don't do the trick, governments usually step in to make it worse. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor once noted — "The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favour by shooting Orville [Wright] down."

For three decades until the mid-1980s, state-owned airlines in India made considerable sums of money for the government until the government started letting in private players enter the civil aviation sector to increase airline penetration in India. Once private players entered the market, more Indians took to the air than ever before and a slew of profitable private airlines emerged during the 90s. As the scenario got more competitive some airlines went bust, some thrived and finally, with the introduction of the low-cost carrier model, there was very little breathing space left. It's important to note that the glory days for airlines was restricted to a period when a duopoly prevailed in the market i.e. a situation where two service providers dominate the industry. They could set prices in consort with each other and compete without having to worry about external threats.

A classic case in point is the U.S civil aviation market. After having seen over 100 airline bankruptcies, the industry finally seems to have emerged out of the dark gory days of the past into a period of abundance. This transition was premised on two developments. An increasingly saturated market and consolidation (through acquisitions) that have left 4 major carriers dominating the industry after a sustained period of brutal price wars. By the looks of it, India currently seems to be at the precipice of a price war, one that's attempting to drive out the old and the infirm by driving prices lower than ever before and creating a cut-throat environment that is already seeing major casualties.

So why does the government think it can bully airlines into further reducing airfares. Simply because it can. In the event that the government forces airlines to cap prices, airlines can't go anywhere. After having invested significant capital, the only seeming exit option for most airlines is declaring bankruptcy or subjecting itself to an acquisition in the event an opportunity presents itself. But outside of that, there is no helpline for airline grievance redressals. So, the prospects of making consistently healthy profits are rather limited so long as the watchful eye of the government looms large over the sector. Derek O'Brien in his tirade against private airline players made another observation. Brien said that the national carrier, Air India had the best luggage policy and that other private airlines should also enhance the baggage limit. Might we also note that Air India is a loss-making entity — an entity whose loss-making operations are funded by the taxpayer? So in a way, people still end up paying for all that excess baggage (even the ones that don't fly), albeit indirectly.

The reason the conflict seems to have risen now can partly be attributed to another volatile element— Oil. Indigo has been profitable for most of its existence partly due to benign oil prices. In a low price environment [Oil] airline players have more breathing space, but as oil becomes more expensive, this margin evaporates in short notice and what we are currently seeing is a fallout of rising oil prices combined with intense competition for customers. When profits disappear airlines get desperate and cost cutting becomes a top priority.

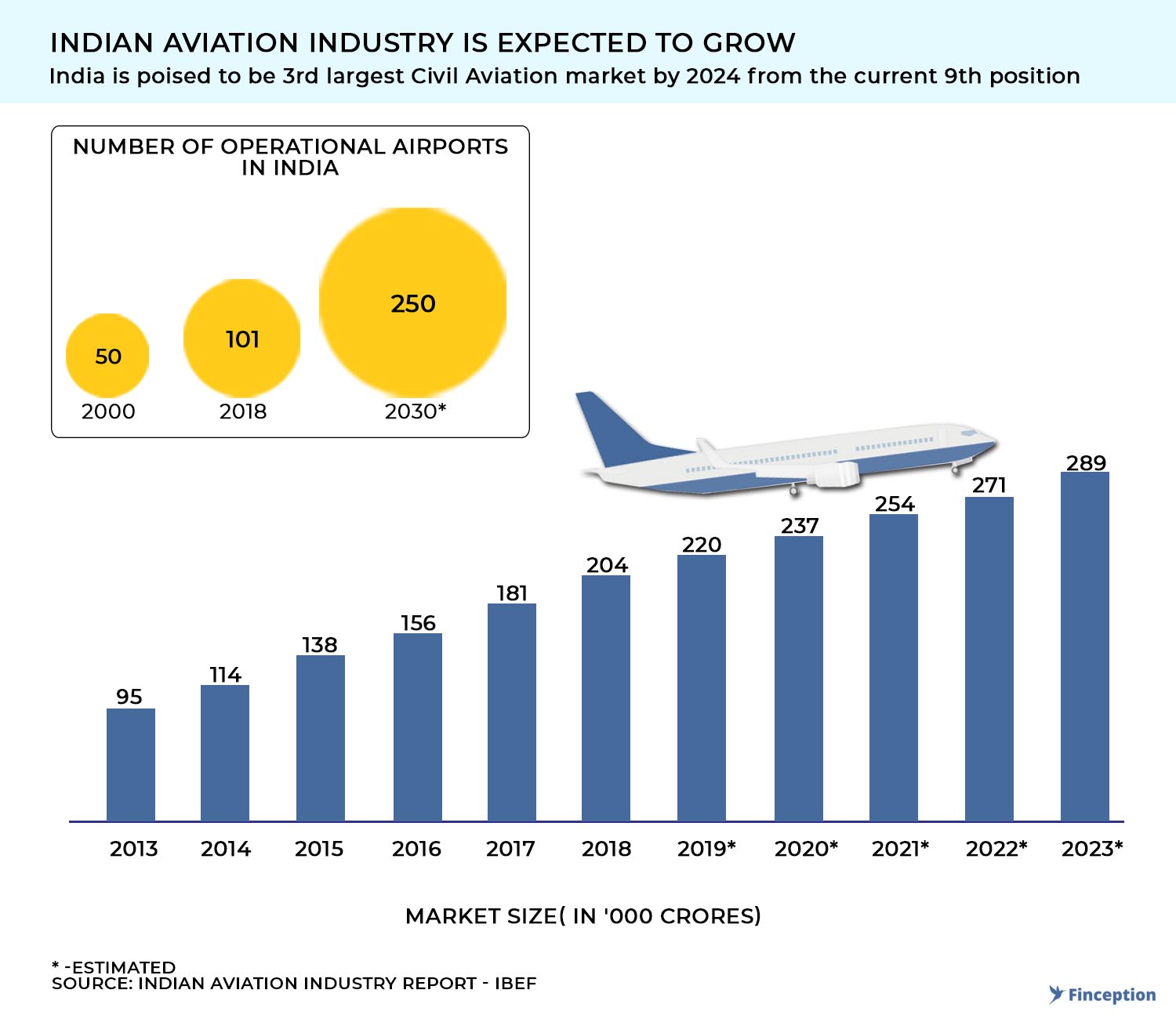

All of this would be irrelevant if it weren't for retail investors and their penchant for extreme risk-taking. People still seem to think that airlines present a lucrative investment opportunity at low-risk levels. This thinking is a by-product of two interesting ideas. The first idea is that the investment is a bet on the great Indian consumption story. Unlike the U.S market, the Indian market is largely underpenetrated and underserved. This presents a unique opportunity. The prevailing notion is that, as more people take to the air, it's likely to bring in more prosperity to incumbents. While this is, in fact, an accurate assessment, it's likely that a growing opportunity will also see intense competition and breed more price wars. Until the industry can finally consolidate or collectively raise prices, the prosperous market conditions are unlikely to bear any consistent fruits.

Note: In 1989, Warren Buffett, purchased $358 million worth of U.S. Airways' debt and it took him two decades to recoup his investment. He vowed to never invest in Airlines again. However in 2017, post consolidation and improving industry margins he bought ~$10 Billion worth of shares of the 4 major U.S air carriers .

The second idea is a spinoff of an investment philosophy popularised by Peter Lynch, the legendary fund manager at Fidelity Investments. The idea is simple. Considering most of the stock market is in the business of serving you (directly or indirectly), anything that piques your interest ought to be seen as an investment opportunity. An extension of this idea is that the more you fly Indigo, the more appealing the investment opportunity becomes. However, it must also be noted that Lynch spent considerable time espousing another idea — asking investors to stay away from glamorous industries. Now clearly that does not mean you should rule out every glamorous opportunity at face value. My point here instead is that you can't view these ideas in isolation. Instead, your bet must be premised on a large gamut of ideas — ideas that can often seem complicated and rife with uncertainties

So there you have it. Investing in airlines requires a great deal of persistence, farsightedness and luck and for the most part, the retail public seems to have had very little success in making significant returns betting on airlines. So maybe it makes sense to look at other opportunities out there? As my friend and business partner often keeps telling me — "The only reason I buy airline stock is because it's a great hedge* against rising ticket prices, otherwise it's a black hole"

. . .

*Hedging is a way of protecting oneself against financial loss

If you want to read more about Operational metrics and the financial aspects of running an airplane have a look at our earlier piece on Jet Airways

Enjoyed reading? Show us your love by sharing...

Tweet this articleReview & Analysis by Pawan, IIM Ahmedabad

Liked what you just read? Get all our articles delivered straight to you.

Subscribe to our alertsDisclaimer: No content on this website should be construed to be investment advice. You should consult a qualified financial advisor prior to making any actual investment or trading decisions. The author accepts no liability for any actual investments based on this article.

READ NEXT

Get our latest content delivered straight to your inbox or WhatsApp or Telegram!

Subscribe to our alerts