Note: The story will largely focus on the U.S market because of the potential opportunity it provides and the increasing focus of Biosimilar companies to gain a foothold in the market

In 1989, Pfizer chemists (pharmaceutical giant) in East England were trying to synthesize a simple molecule drug that they thought might treat high blood pressure and chest pain. The low priority project had pretty disappointing results initially and showed little to no promise. In 1993, during a clinical trial, researchers were trying to study the effects of the drug on a group of Welsh Mineworkers. After a disappointing review, the researcher finally asked if the participants noted anything else they might want to report. One of the men put up his hand and said, "Well, I seemed to have more erections during the night than normal," and everybody else kind of nodded and said, "So did we." On that gloomy evening in South East England, the world had finally chanced upon Viagra, the miracle drug. It took another 4 years for the FDA (Food and Drug Administration, USA) to approve the magic pill, but at the end of it all Pfizer had in its hands what is often touted as a "blockbuster drug."

The point here is that success in this market is deeply intertwined with the research and development process that characterizes the pharmaceutical industry. It might take 5 years for you to develop a new drug and you might still need another 10 years to clinically test the product and gain approval from the regulatory agencies. This is an extremely capital intensive process and the only way to remunerate the investment of the pharma company is to protect the investment through patent protection. Viagra's product patent lasts a whole 20 years (US) and no other company can sell the same compound during that time. This way the companies can be incentivised to invest more in research thereby ensuring a steady supply of new innovator drugs.

Once the patent expires, however, copycats can market their own version of the drug. These copycat drugs are called generics and companies can replicate the manufacturing process with relative ease. In order for a company to market a generic, the FDA must agree that the generic is interchangeable with the innovator product and that it contains the same active ingredient. Because of the relative simplicity involved in manufacturing generics, the industry also breeds intense competition. This increasing competition has interestingly spun off a new proxy war of its own with its own cast of complex characters.

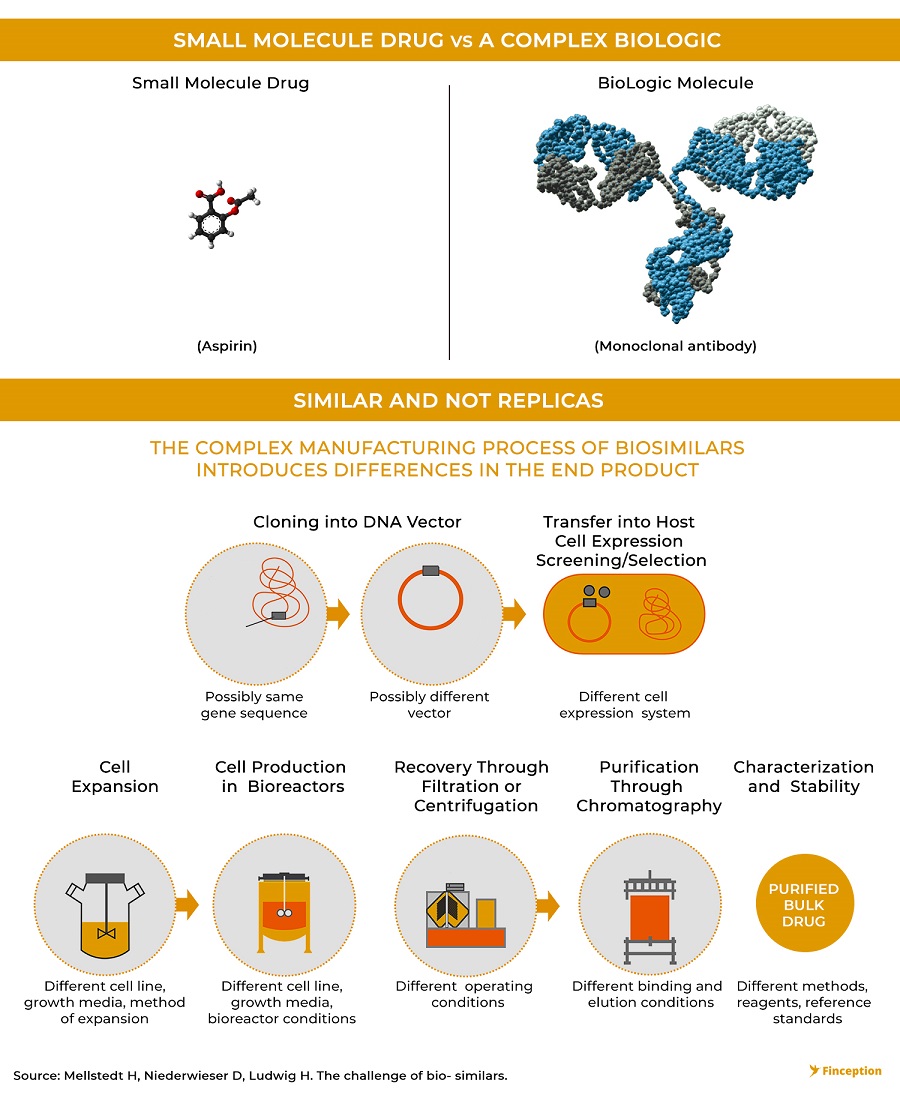

Ever since modern medicine started to emerge post the Industrial Revolution, simple molecules have been used to treat most diseases. While these formulations were highly effective against some illnesses, it was proving particularly ineffective against more complex diseases like cancer. Our immune system has evolved over millions of years to specifically defend against intruders by finding and destroying anything that's not supposed to be inside our bodies. But cancer isn't like most diseases. It's not caused by an invasion of a foreign pathogen. Instead, it's a byproduct of rogue cells within our body that don't necessarily act the way they should. To this end, using simple molecules to defend against a barrage of mutating versions of our own cells is an exercise in futility. In the process of killing the bad cells, these drugs will simultaneously annihilate the healthy cells too. So the cut-slash-kill method isn't particularly effective. What we instead need is a 'biologic' or a complex protein isolated from natural sources that can mimic our immune cells.

Although initial attempts to replicate and genetically modify antibodies failed quite miserably, the field of biologics has begun to show considerable promise since the turn of the century. Also, the advent of biologics isn't a particularly new phenomenon. We have had vaccines for a good half century now and considering most vaccines are complex living agents that resemble a disease-causing microorganism, they fit under the ambit of biologics pretty well. However, it's only in the last 25 years that new developments in genetic engineering/recombination techniques and targeted therapies have begun to open up new opportunities and this, in turn, has breathed new life into the field of biologics and with it, its copycats — biosimilars.

Unlike small molecule drugs like Viagra that can be chemically synthesised using a straightforward approach, biologics are harvested from living cells and are often produced using complicated manufacturing processes. Most modern biologics are assembled inside vats — or bioreactors — that house genetically engineered microbes or cell cultures and can often take a whole decade of research to perfect. So replicating the process isn't exactly a cakewalk and often times the copycat version (biosimilar) can differ from the innovator biologic.

Michael Yang, President of Immunology at Janssen Biotech described it this way — "biologics are living proteins, and living proteins can't be copied, in the same way, that one oak tree is different from another, even though they are both classified as oak trees." A biosimilar is not equivalent to the original biologic, instead is highly similar in the way that it interacts with the human body. The design and creation of a biologic drug is complicated enough that a biosimilar isn't going to be precisely the same as a biologic. So the FDA has to be extremely meticulous whilst approving the drug and ensure that it acts the same way as the reference(innovator) biologic would. So in addition to the lengthier, more expensive development process, biosimilars also entail a more time-consuming approval process characterised by several phases of clinical trials. While multiple Indian companies have forayed into manufacturing and marketing generics in developed markets, only one Indian player seems to be trying to make a dent in the biosimilar space.

Biocon's Biosimilar segment has shown growth of more than 100% for 9 months ended, FY19. The segment's operating margin, which was in the red until last year, has now moved up to 30%, buoyed by the launch of its first biosimilar in the US market

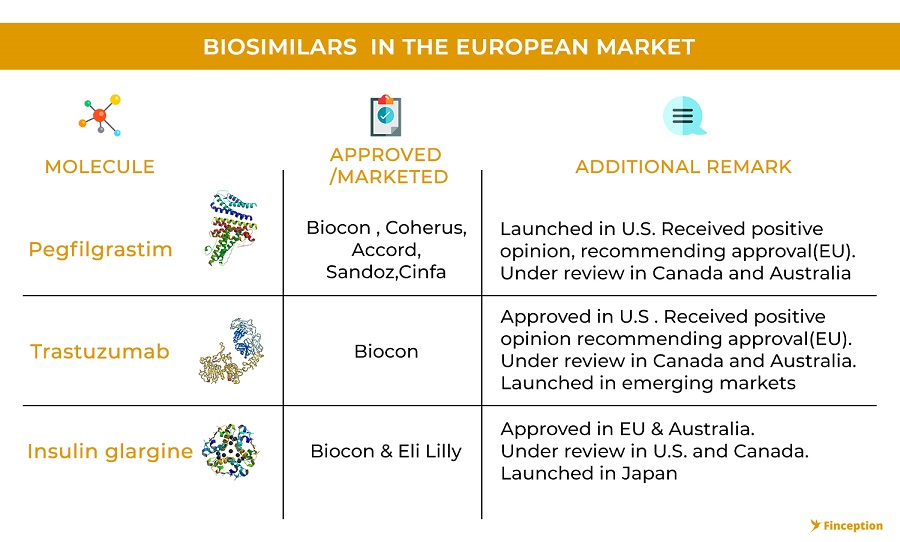

Biocon is an Indian pharmaceutical manufacturer that is gradually transforming itself into an innovation-led biosimilar developer. Although 85% of it's existing revenues (FY 18) are attributed to other segments including generics and research it's made large strides in the field of biosimilars and is increasingly looking towards consolidating its position as one of the market leaders. To this end, it has collaborated with a UK based pharmaceutical giant Mylan to form a joint venture to benefit from its strong commercialization penetration across the globe. The partnership sets up an arrangement for jointly developing, manufacturing, supplying and commercializing biosimilars. While Mylan holds the marketing/commercialization rights for the developed markets like the US, Canada, Japan and EU. Biocon holds the exclusive rights to market the products in emerging countries.

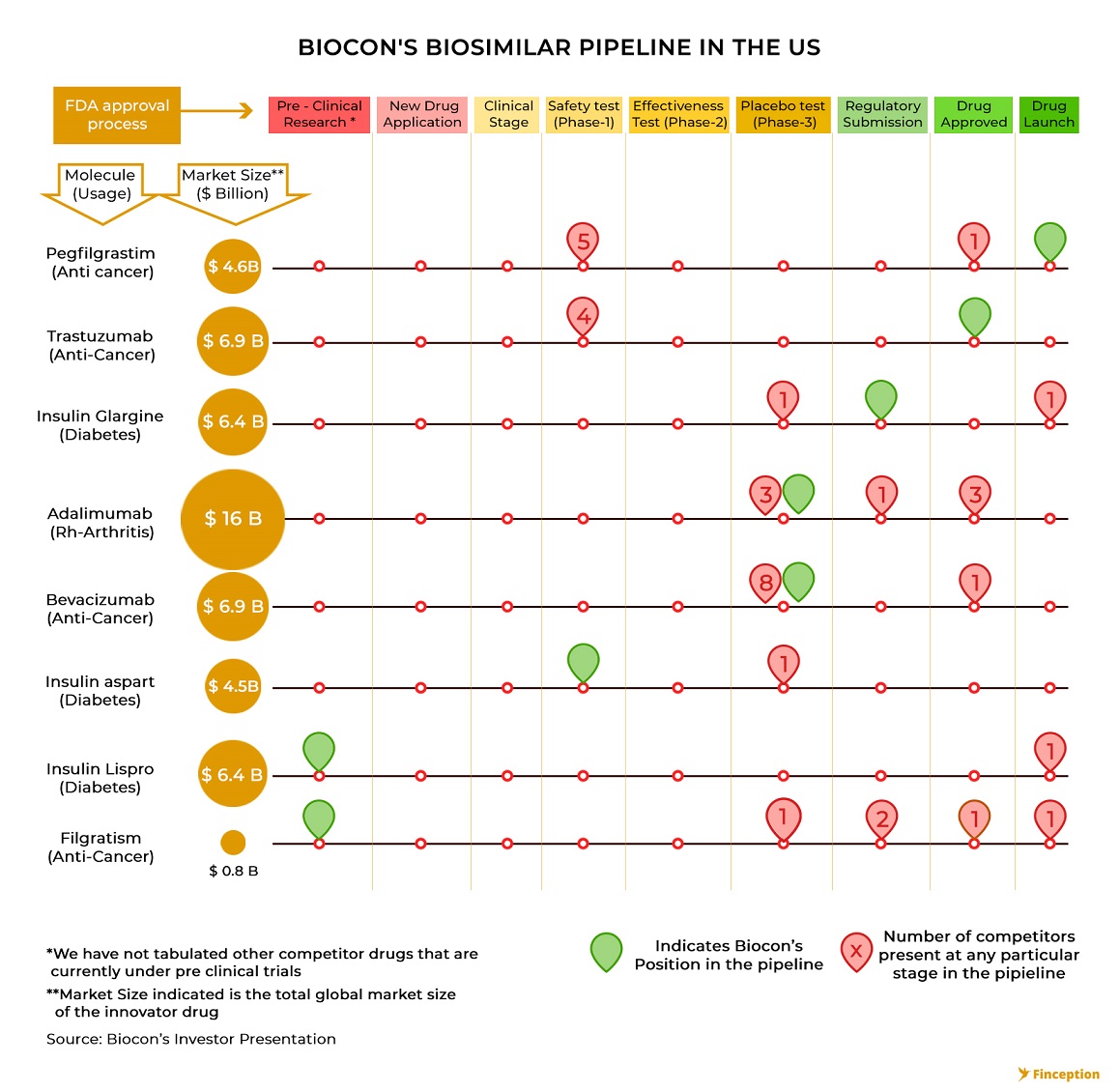

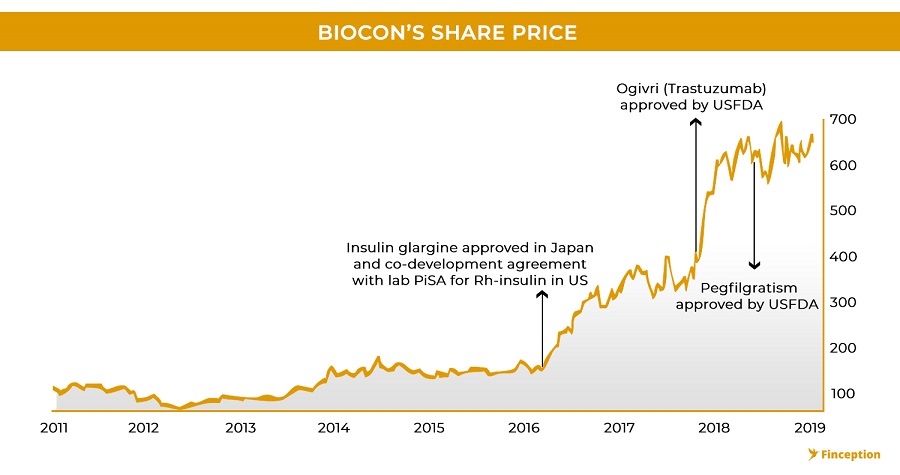

While Biocon has been investing in developing and refining its global biosimilar pipeline for the past few years it's only recently that investors began to take notice of all the underlying potential. The product pipeline is characterised by different stages of the research and development cycle and the further ahead a drug is in this pipeline the more valuable it becomes. Interestingly, the product pipeline also forms the cornerstone of the investment thesis most people ascribe to pharma companies.

This thought is also an extension of the efficient market hypothesis wherein proponents believe that all available information is already reflected in the stock price. With pharma stocks, investors don't necessarily wait for drug companies to market and sell their product. Instead, they closely monitor the pipeline and the movement of drugs across various development stages. In the event that a drug moves from clinical trials to regulatory approval, investors start bidding up the price of the stock to reflect this new information. When Biocon (in partnership with Mylan) became the world's first biotech company to receive US regulatory approval for a particular biosimilar (Trastuzumab), the stock rallied close to 40% almost instantaneously. So even before the drug is marketed, even before a single penny is ever earned, even before it becomes fully apparent that the drug will, in fact, receive regulatory approval, investors will have already ramped up the prices to reflect the anticipated earnings and this offers insight into another riddle — as to why Biocon trades at such premium valuations. While one might venture that this particular feature is exactly what is telling of an overvalued stock it's also quite possible that the valuation currently reflects the robust pipeline that Biocon boasts.

This isn't a feature unique to Biocon. Another comparable biosimilar player, Celltrion, a South Korean company that ventured into this space much earlier has seen its value compound by as much as 6 times. This compounding translated over a period of 8 years as when its product pipeline showed incremental developments

However, the market poses its own unique set of challenges. First, the U.S market is notorious for its slow regulatory process. Second, there has been very little systematic effort to educate physicians and patients who are concerned about biosimilar safety and efficacy. Finally, originator companies have honed their patent litigation and preemptive competition skills, so much so that lawyers have a new name for it now — The Patent Dance

"[It's like a] a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma," — A frustrated District Court judge while interpreting the various provisions of the US Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act), which among many things also offers patent protection

In a bid to sort out any potential patent disputes, the US BPCI act devised an elaborate exchange mechanism for both the innovator and the biosimilar to resort to a formal process of dispute resolution. As they engage in the Patent Dance, both parties exchange information about their formulations and manufacturing processes to ensure that the biosimilar applicant does not infringe on any patents of the originator and the originator, in turn, promises not to sue the biosimilar for infringements in the future. Although in theory, this should have alleviated much of the legal concerns surrounding biosimilar launches, things haven't exactly worked out that way.

Companies that are overly reliant on a small portfolio of blockbuster drugs go to extreme lengths to protect their intellectual property by filing several patents that might last well over the average 20 years. In one notorious case, AbbVie, a pharmaceutical giant has secured more than 100 patents to prevent anyone from attempting to copy its innovator biologic and has warned copycats of expensive litigation fee in the event they don't pay heed to the warnings. While companies are usually only ever accorded a single product patent, they get around this inconvenience by patenting the formulation and manufacturing processes as well. So when a biosimilar applicant decides to [patent] dance with the originator in good faith and exchange sensitive information, the originator begins to use this new information to further strengthen his patent claim and litigate anyway. And this brings us to the second question. If the process is so detrimental to a biosimilar applicant why dance in the first place?

After the Supreme Court Judgement confirmed that innovators cannot force biosimilars to engage in the patent dance, pharmaceutical companies have resorted to another technique — Blind litigation. In March 2018, Amgen, a pharmaceutical giant sued Adello Biologics, a US-based biosimilar maker, for patent infringement in connection with a proposed biosimilar of Amgen's innovator drug. Adello elected to skip the patent dance entirely and did not provide any information to Amgen regarding its biosimilar or how it is manufactured. Absent any information from Adello about its biosimilar, Amgen asserted 17 patents against Adello blind. The patent dance protects biosimilars from such frivolous litigation by severely limiting the scope. If Adello would have danced, Amgen in all likelihood would have limited its suit to a few patent assertions and this, in turn, would have provided more clarity to the biosimilar company on how to best tackle the issue. Its also becoming increasingly clear that despite the obvious downside of providing a potentially litigant with ammunition by exchanging patent information, more biosimilar companies are in fact participating in the dance, albeit by still keeping some information proprietary thanks to the loose wording of the BPCI Act.

All of this is important because Biocon (through its partner, Mylan) is at the precipice of launching its first wave of biosimilars in the developed markets. On July 2018, Biocon launched its first biosimilar, Fulphila in the U.S market and in the process became the first company to market a biosimilar for the famous innovator drug Neulasta(Pegfilgrastim). There was however very little fanfare in the Indian stock markets but it's a noteworthy development for 2 reasons. First, there are only 4 biosimilars currently sold in the US market, (although many others are awaiting approval). Second, in its 3rd quarter earnings update, Mylan stated that the drug already (within 3 months) had an 8% market share in the pre-filled syringe segment which forms close to 50% of the entire Pegfilgrastim market. This is noteworthy because previous biosimilar launches have had mixed reactions in the US. While some biosimilars (Sandoz's Xarxio) have captured close to 35% of the US market with as little as 15% discounts (over~ 3 years), others have failed to make any dent in the market despite resorting to deep discounts. This is further complicated by how an innovator company chooses to respond in the face of biosimilar competition.

In some European countries the market size has shrunk by about 70% after the launch of biosimilar owing to steep discounts and rebates

In a bid to protect its blockbuster innovator drug Remicade, J&J decided to offer rebates to insurers and essentially locked out biosimilars from the market. This move, while limiting entry for potential biosimilars simultaneously reduces the market size and does not really benefit anybody. Others have simply decided to litigate and bog down biosimilar companies from even trying to market their product. But perhaps what has eluded most investors is that despite Biocon's (Mylan) successful launch of Fulphila, it was an at-risk launch, meaning Mylan is still involved in a patent dance with Amgen over two patents claiming methods of purifying proteins used in manufacturing biologics. Although Mylan and Amgen are trying to resolve the litigation through court-sponsored mediation, this story is far from over and that's why we had to tango with you as we struggled to explain the complex dynamics of the Patent Dance.

It's not just one drug. Biocon also became the first company to receive approval to market another drug, Trastuzumab, in the U.S. This time, instead of engaging in expensive court proceedings, they decided to arrive at a settlement and licensing agreement with the innovator company, thus providing a clear pathway for a global launch of its biosimilar. The product patent for the innovator drug expires in mid-2019 and you will likely see Biocon launching its biosimilar version soon after, hopefully without a hitch. So, all in all, it seems that the larger theme that's currently emerging in the biosimilar space is that the revolution is here to stay and it's no longer a matter of 'if' but 'when'. The success of most companies will perhaps be built on the backs of strategic partnerships and alliances that companies build and Biocon definitely looks like a promising opportunity.

How promising? We don't know.

But the company has stated its goal loud and clear. 1 Billion Dollars in Revenues from its Biosimilar division by 2025.

The company also recently entered into a strategic alliance with Sandoz, the generic and biosimar branch of the drug major Novartis. The details of the deal are still confidential

. . .

Enjoyed reading? Show us your love by sharing...

Tweet this articleReview & Analysis by Pawan, IIM Ahmedabad

Liked what you just read? Get all our articles delivered straight to you.

Subscribe to our alertsDisclaimer: No content on this website should be construed to be investment advice. You should consult a qualified financial advisor prior to making any actual investment or trading decisions. The author accepts no liability for any actual investments based on this article.

READ NEXT

Get our latest content delivered straight to your inbox or WhatsApp or Telegram!

Subscribe to our alerts