Published 23rd Mar, 2019

When we first did our story on Eicher, I remember thinking what the theme surrounding the story was going to be. It should have been pretty self-evident. Eicher's was a classic comeback story, a sort of turnaround that's so cliched in literary circles that I was having second thoughts about running our first ever story with this idea. Eventually, I decided to drop the whole comeback theme for a more modern approach of "Good to Great". However, with the Indian stock market behaving the way it has been off late I must confess that it's becoming increasingly hard to keep the good old "comeback theme" in the deep freezer.

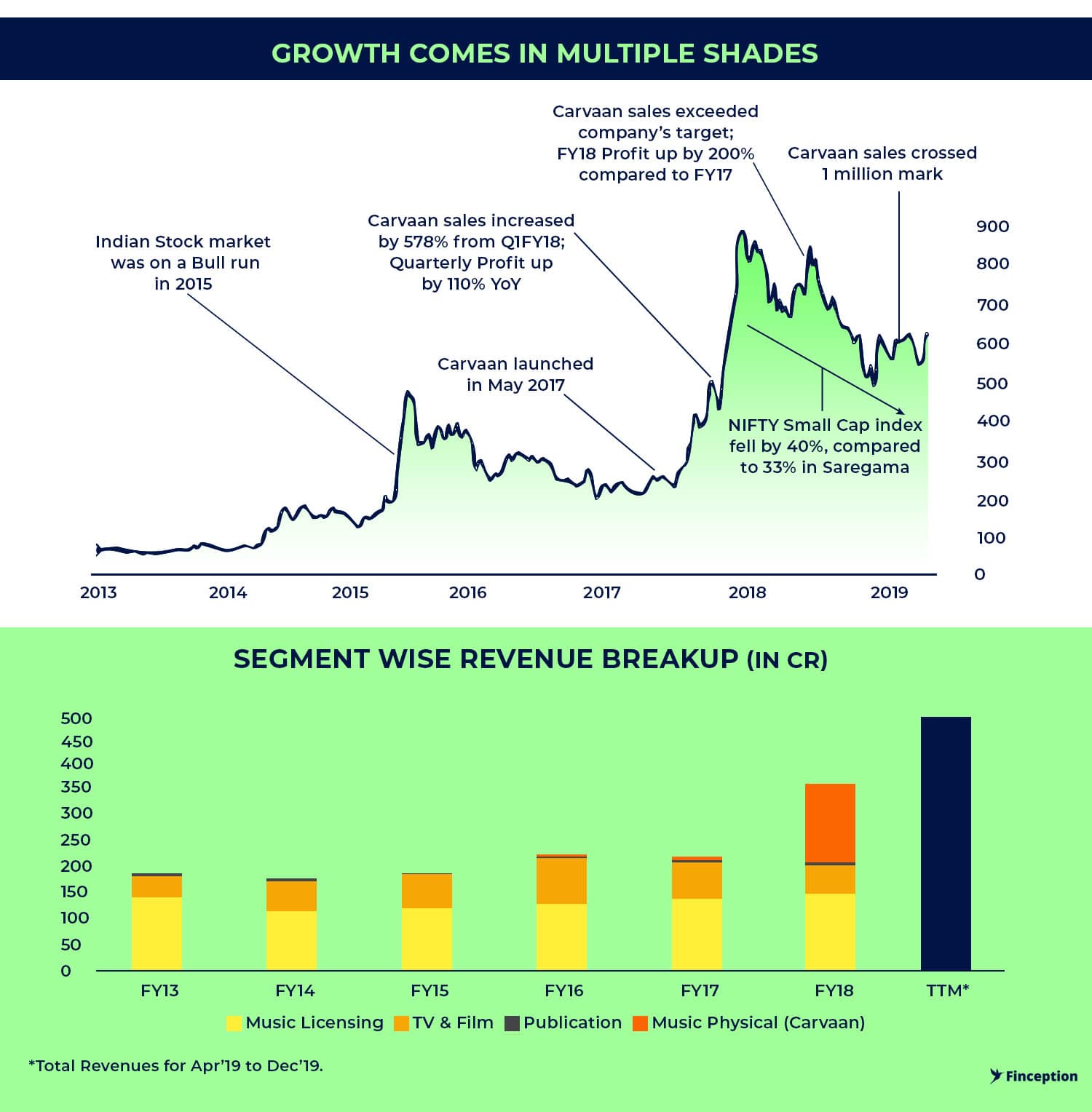

And so when I heard Saregama's story I was pretty excited because this was my chance to pull out the old classic, but with a twist. Unlike other stories we've covered, Saregama's story of change is premised on both internal and external causal factors. More often than not we see something drastic happen because the company does something amazing or if there's an unexpected change in the industry elsewhere. Very rarely do we see both happen at the same time. So this comeback story is special. However, before we get to the nitty-gritty, some additional context.

Saregama started as a music label in 1901 and recorded some of its first songs the same year, which also happened to be some of the first songs ever recorded in Indian soil. Eventually, it went on to have a virtual monopoly in recording and distributing music and became the most dominant music label post-1960. However, change is inevitable. Although it still kept recording with major artists and acquiring rights to good music amassing a catalogue of well over 100,000+ songs (in multiple languages) it was evident that the company was beginning to lose some of its sheen and by the turn of the millennium Saregama was no longer the dominant force it once was. It's at this point that observers were casting aspersions on Saregama's ability to acquire rights to good music. This was partly attributed to increasing competition from the likes of T-Series and the rest to the growth of other independent music labels. The contention was that Saregama was overly reliant on its pre-2000 music library and for a company depending on its retro music catalogue, growth can be hard to come by, especially in an increasingly digital world.

While there's some merit to this argument it is still an incomplete assessment. It's true that Saregama is largely known for its retro library, but its music catalogue post-2000 is not shabby at all. 30% of its total library is made up of songs that were recorded this millennium and some of its top hits come from this lot. Although increasing competition has dented the company's prospects in recent years, Saregama is still a force to be reckoned with. However, as we have already noted it is also true that the glory days of the yesteryears are now a thing of the past. In a digitised world, there was another prominent scourge that washed away profits in tides — Piracy. Why would anyone buy good music when you could download most songs at the click of a button online for free. In a bid to curtail this pervading menace, record companies started spending significant resources in battling privacy. Unfortunately, they were seeing very little return for all the effort spent, even when they took large price cuts and started making their content available online, legally for a fraction of the price they were originally sold at. This is especially evident if you were to look at the licensing revenue for the company in recent years. Between 2012 and 2016, the company made anywhere between 120 Cr. to 140 Cr. and it was increasingly looking like Saregama was teetering at the edges of uncertainty for far too long without showing any solid growth prospects. Nobody could predict with any reasonable degree of accuracy how much money Saregama could make out of licensing their existing catalogue any given year and in the markets, that's a problem. However, all that changed when the management decided to monetise its fabled music IP in the most uncanny way imaginable.

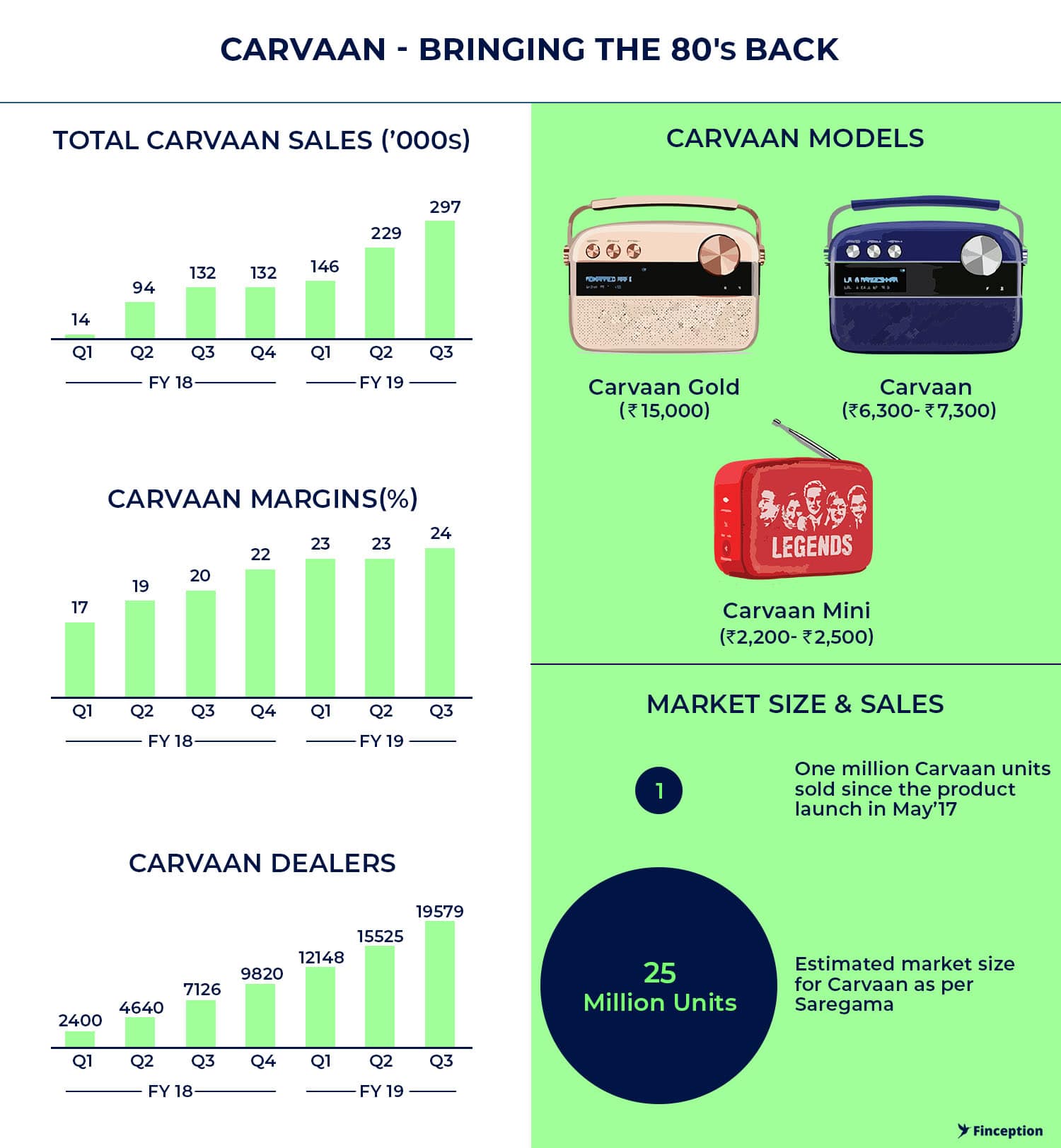

Carvaan is a portable digital music player that looks and feels like an old transistor radio but works like a modern music player would. It's got Bluetooth connectivity and a USB port to go with it. Although the tech and the aesthetics help in elevating the status of this music player and differentiating it from other music players out there, the real differentiation is what's inside of it. The 5000 songs that were handpicked based on extended research is what most people are buying when they're purchasing a Carvaan unit. This renders all competition void because nobody can replicate the unique selling proposition.

The idea looks genius. But if I were to go back in time and write about this at the time of the release of this product I would have laughed at the mere suggestion of people buying radios at Rs. 5000, especially at a time when radios were considered relics of the past. However, looking back, it probably does make sense. The real crux of the issue is that people are still willing to pay for convenience and accessibility. Baby Boomers and Gen X(people born between 1946 and 1979) aren't as adept at technology as millennials are and even when piracy was at its peak, these people weren't the ones exploiting the lax rules. They were being completely being left out. As physical cassettes went out of fashion, they found it increasingly hard to keep up with their favourite music — stuff from the '70s, '80s, '90s and maybe the 2000's. Another interesting thing to note is that the product was actually marketed to millennials, in the hope that they would see merit in gifting this to their parents or even grandparents. But either way, Carvaan is a runaway success as of today. It's sold near 1 Million units in just over a year, added 145 Crores to its top line (which forms roughly 40% of its revenues) and the company says it's got a prospective target userbase of 25 Million based on their market research.

Now it's important to note that as the company gets closer to their target of 25 million units, it could mean that they might have to spend more on marketing (as the initial sales were driven through word of mouth) or they might have to reach dealers across multiple cities and penetrating such areas might mean a deterioration in margins. However, you can't fault Carvaan for what it's currently doing especially if it keeps adding hundreds of crores to the company's top line. Bear in mind that this initiative to improve accessibility to their music IP was driven by the company — Saregama, however, unbeknownst to them another major force was also colluding to drive home accessibility at the same time — Jio.

Point of Interest : The company has also launched newer variants of Carvaan trying to tap into both the premium and the affordable segments

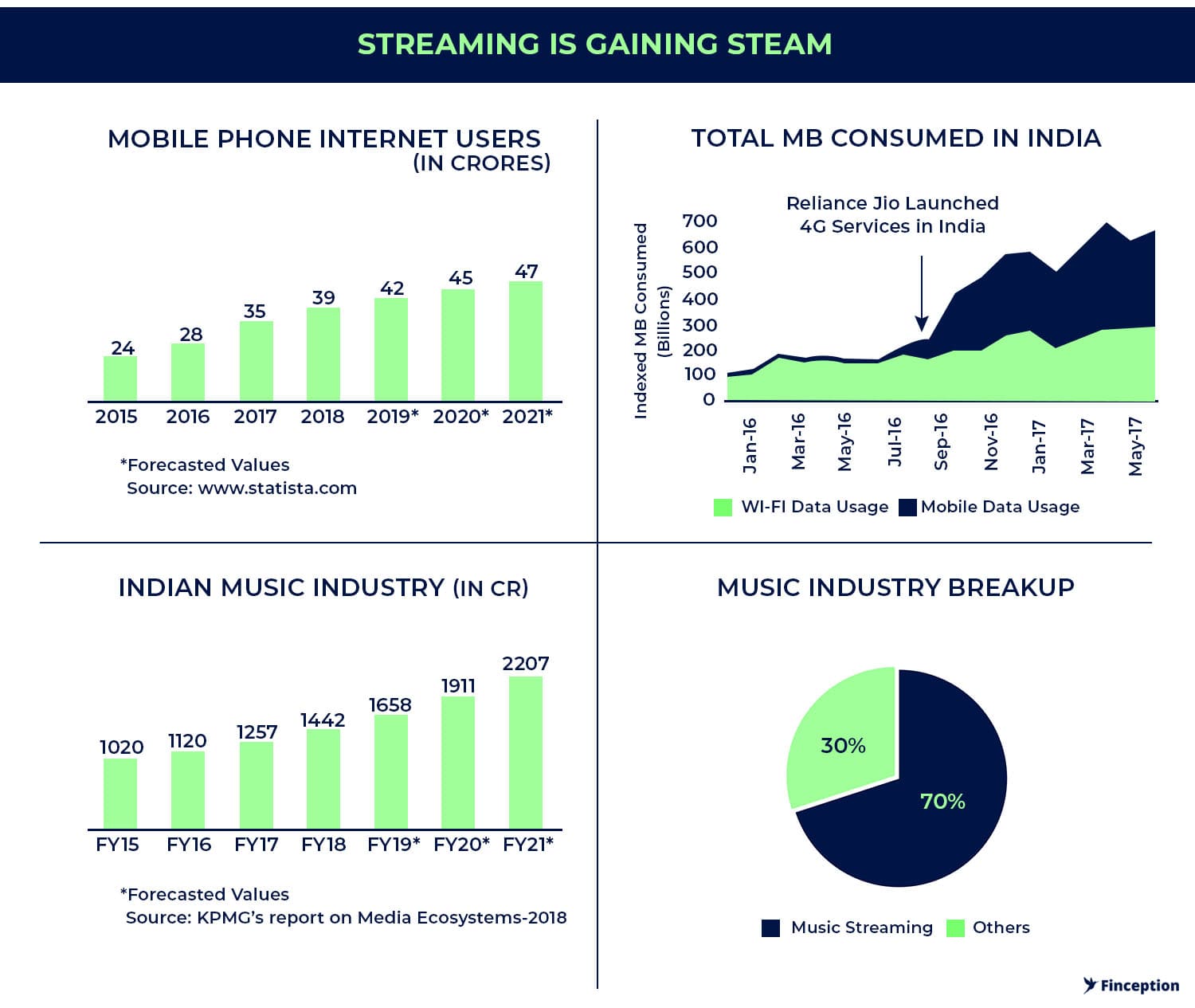

India's internet scene changed overnight in September 2016, when Reliance Industries shelled out $35 billion to launch India's first 4G network, Since then, Monthly data traffic in India per user has jumped 570% according to Morgan Stanley. With the cheap data now freely available, the music industry was going to change forever. For one, it gave people unprecedented access to the internet. More people accessing the internet inevitably meant more people spending time and money on digital music. The IFPI — representing the recording industry worldwide, found in a recent survey that Indian consumers spend 21 hours every week listening to music. This is considerably higher than the global average of 18 hours per week. The data binge that followed Jio's entry simply provided further impetus to an already music crazy audience.

Second, it made streaming more attractive. Better connectivity and streaming services (Gaana, Saavn, Wink) based on the freemium model meant people no longer had to download or share songs illegally. Although piracy is still a major concern, it's provided music companies like Saregama with a lifeline. Consider, for example, Youtube — The Company currently has 23 channels with a subscriber base of 10 Mn users and it's interesting to note that monthly views have grown from 0.5 Mn to 300 Mn in just 4 years. Although some people seem to suggest that the initial euphoria has now abated, anecdotal evidence stands in stark contrast. T-Series, another competitor buoyed by the ever increasing Indian online presence has usurped Pewdiepie as the topmost subscribed channel on Youtube with close to 91 million subscribers as of today. It's not just Youtube, other streaming services are garnering considerable interest as well.

In a panel discussion hosted by the IMI (Indian Music Industry), Sachin Singhal, Chief business officer at Airtel's Wynk Music, said Indian music streaming services had 12 to 15 million Daily Active Users according to Firstpost. IMI chairman Shridhar Subramaniam also noted that one of the aims is to have 400 million active users (MAU) "on legal music services by 2020" (current userbase is pegged at around 100 MAU). That might seem like a rather lofty goal, but in a way, it points to the massive ambition streaming services harbour. With the likes of Google, Amazon, Jio, Gaana and Spotify all entering the fray, perhaps the goal is not as ludicrous as it might first seem. But the real question is how all of this aids Saregama and the record labels that own the music catalogue.

Not everybody is convinced however that the recent developments in the streaming industry are a sign of good things to come. The first argument is that despite streaming services gaining in popularity we ought to see a decline in revenues from licensing old music. The suggestion is that the cost of content acquisition for streaming services is already high (of the overall cost incurred by a streaming platform, more than 50% goes into content acquisition). And as these services try and build a sustainable model they will haggle with the music IP owners i.e. Saregama to cut prices, which will inevitably drag licensing revenues.

While this argument does hold merit in the long run, it's not something that is of particular concern over the immediate future. The reason is very simple. Currently streaming services, by and large, try and differentiate themselves based on the size of their music catalogue. However, as time progresses, most of these services will converge to a point where they will all have a similar offering and will include almost every song on their platform. As users begin demanding a more complete music catalogue, the bargaining power will rest with the record labels (Saregama, T-Series etc.), during which time you should ideally see an increase in licensing revenue. However as basic economic axioms dictate, eventually the competition between streaming services will increase to a point where the weaker players will be forced to quit or join hands with the larger incumbents. At this stage of the business cycle, you will have an oligopolistic market place, characterised by maybe 2–3 players and the bargaining power should eventually revert to the streaming services.

Based on where we stand today, it is easy to see that the competition is now only beginning to simmer and that means licensing revenues should ideally trend upwards. And despite all the talk of licensing revenues flatlining, the immediate evidence seems to reinforce the idea that such a predicament is still a few years away. The second argument from the sceptics is that ad revenues from streaming services are still dismal and completely out of line when compared to global standards. Despite Saregama and T-Series garnering millions of views on their Youtube channel, they don't make nearly as much money as their foreign counterparts. This is patently true. Consider, for example, CPM or "cost per 1000 impressions," — a metric that indicates the price advertisers pay for running their ads a 1000 times. In India, CPM rates are markedly low. This could be attributed to the low penetration of digital advertising in India. Advertisers still spend considerable money on traditional channels, like the media or print and only reserve their digital budgets after accounting for the other options. However, if one were to look at how this dynamic is shaping up as we move closer to tomorrow, it's not hard to see advertisers cosy up to a digital future as Indians start binging on more data. Although ad revenues from digital medium might not tally up the way record companies would have liked, they too are likely to trend upwards in the near future.

The final piece of the comeback triumvirate is a flourish from the company's movie-making arm — Yodlee Films. Unlike traditional production houses that deal with big budgets and nationwide theatrical release, Yodlee wants to cater to a very different segment. Saregama says that the objective is to make movies that are driven by strong themes and powerful stories and not necessarily box office stars. The average budget is at about 2–4 crores per movie and they keep the costs low by adopting a profit-sharing model with actors and directors.

The big catch here is that these movies are mostly sold to OTT platforms who are looking for good content. They've already sold 5 movies to Netflix this year and they recently made a deal with HotStar for an additional 10–12 movies the next year. OTT platforms benefit from making this content exclusive to their platforms. Considering OTT platforms are on the lookout for original content, that looks and feels different from mainstream Bollywood and Hindi soap operas - it's another ploy to attract the burgeoning digital audience that's moving away from the more traditional entertainment experience. Now bear in mind that Saregama does not disclose how much money it's made from Yodlee and so it's hard to make any assessment about the future profitability of this division and its impact on the stock price. However, it's safe to say that this is another bold move from a company that everyone once though ought to be cast aside to be included in the history books.

And so here we are. The past 2 years have probably been some of the company's best years ever and no I am not saying that to induce shock and awe I genuinely do believe it. The company has not only found a magical new way to sell its IP through Carvaan, but its also embracing a future that's changing its core DNA as we speak and that for me is telling. As someone once said — Progress is a function of change and it seems as if the grand old company is changing right before our eyes. Will progress follow through? That's a question I will leave to you.

We have relied on excerpts from “Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought” by Andrew Lo and Nate Silver’s “The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-but Some Don’t”, to put this story together

. . .

Enjoyed reading? Show us your love by sharing...

Tweet this articleReview & Analysis by Pawan, IIM Ahmedabad

Liked what you just read? Get all our articles delivered straight to you.

Subscribe to our alertsDisclaimer: No content on this website should be construed to be investment advice. You should consult a qualified financial advisor prior to making any actual investment or trading decisions. The author accepts no liability for any actual investments based on this article.

READ NEXT

Get our latest content delivered straight to your inbox or WhatsApp or Telegram!

Subscribe to our alerts