Published 16th Feb, 2019

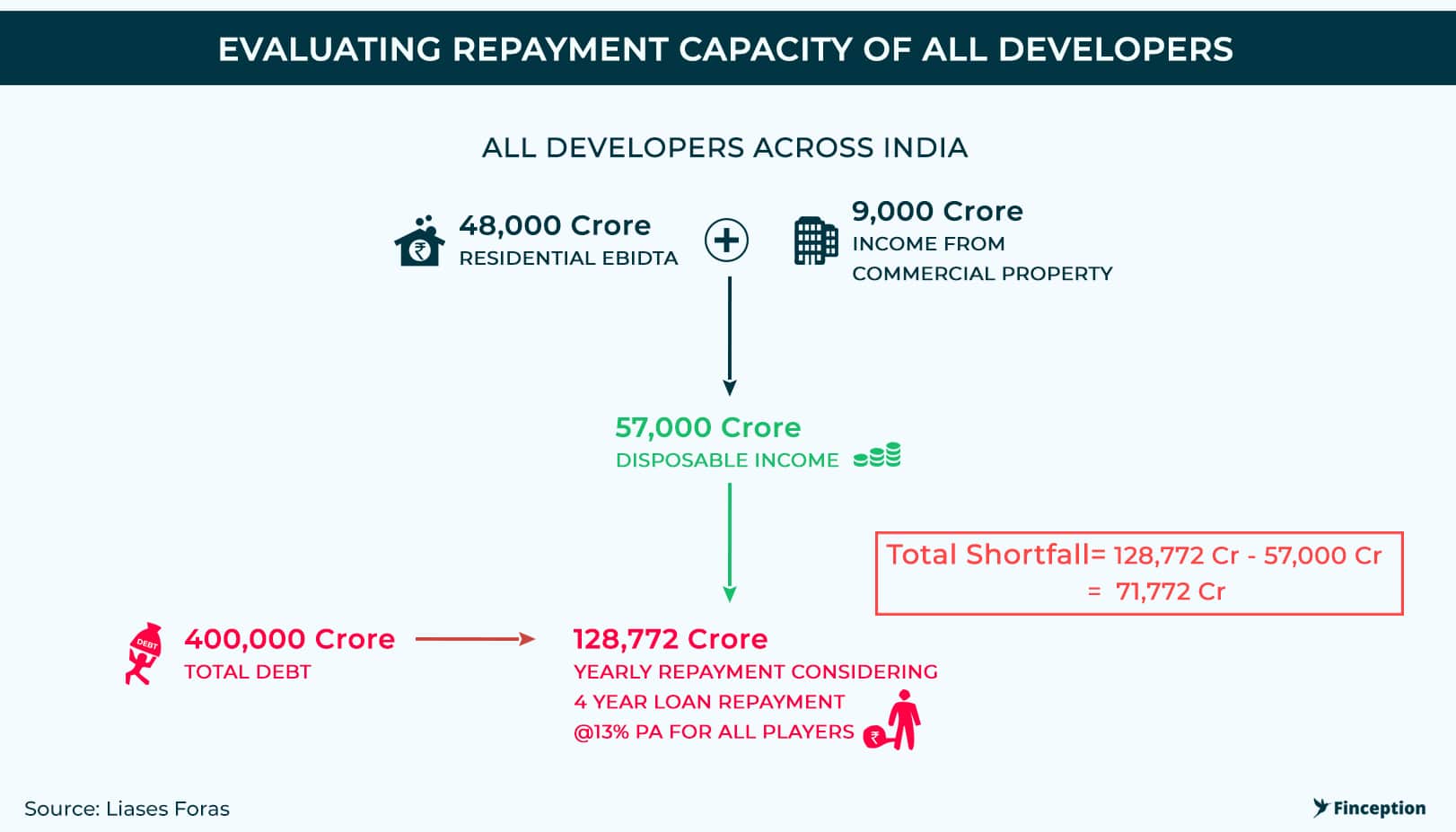

On February 4th a small independent Real Estate research company, Liases Foras had a very exciting story to tell. Outside of a few TV channels and some business news agencies, the story did not elicit a lot of interest but it was an explosive story nonetheless. In a White Paper published the same day, the research firm had calculated the total disposable income all Real Estate developers were poised to make this year and juxtaposed it with their interest obligations. The numbers were making a startling claim. Real Estate developers were not going to meet their interest payments unless they increase their margins by a substantial amount.

This situation was akin to the dreaded tale of the IC1 companies — companies who had borrowed gargantuan amounts through Public Sector Banks (PSB) , companies with an interest coverage (IC) ratio of less than 1 (who did not make enough to pay back interest on their loans), companies that spawned during the infamous Infra/Power Sector debacle after which the true scale of the NPA problem came to light. If the report from Liases Foras is, in fact, accurate, then the suggestion is that more Real estate Developers are likely to default unless there is large scale intervention. Our story today tries to piece this puzzle together and see if there's any merit to this claim.

The seeds were sown during the economic boom of the 2004–2008 era when GDP growth was constantly surging at 9–10 per cent every year. In a bid to exploit the growth opportunities available, crony capitalists started making grand plans without infusing a lot of their own money. On the back of excessive borrowing sprees, they launched new projects worth lakhs of crores, particularly in infrastructure-related areas such as steel, power and Real Estate setting off the biggest investment boom in the country's history. Until in 2008, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) threatened to ravage the entire world economy.

India, however, emerged out of the GFC relatively unscathed. But growth rates moderated. The most affected were companies that had overstretched themselves after having borrowed large sums to commission expensive projects. Costs ran well above budgeted levels and revenues did not meet expectations. This should have been the moment of reckoning for Real Estate companies. After all, developers had borrowed excessively in the hope that the construction boom would continue perpetually, added large amounts of unproductive inventory and were under significant stress. As if these problems were not enough, borrowing costs increased sharply. Firms that borrowed domestically suffered when the RBI increased interest rates to contain inflation. And firms that had borrowed abroad when the rupee was trading around Rs 40/dollar were devastated when the rupee depreciated, forcing them to repay their debts at exchange rates closer to Rs 60–70/ dollar.

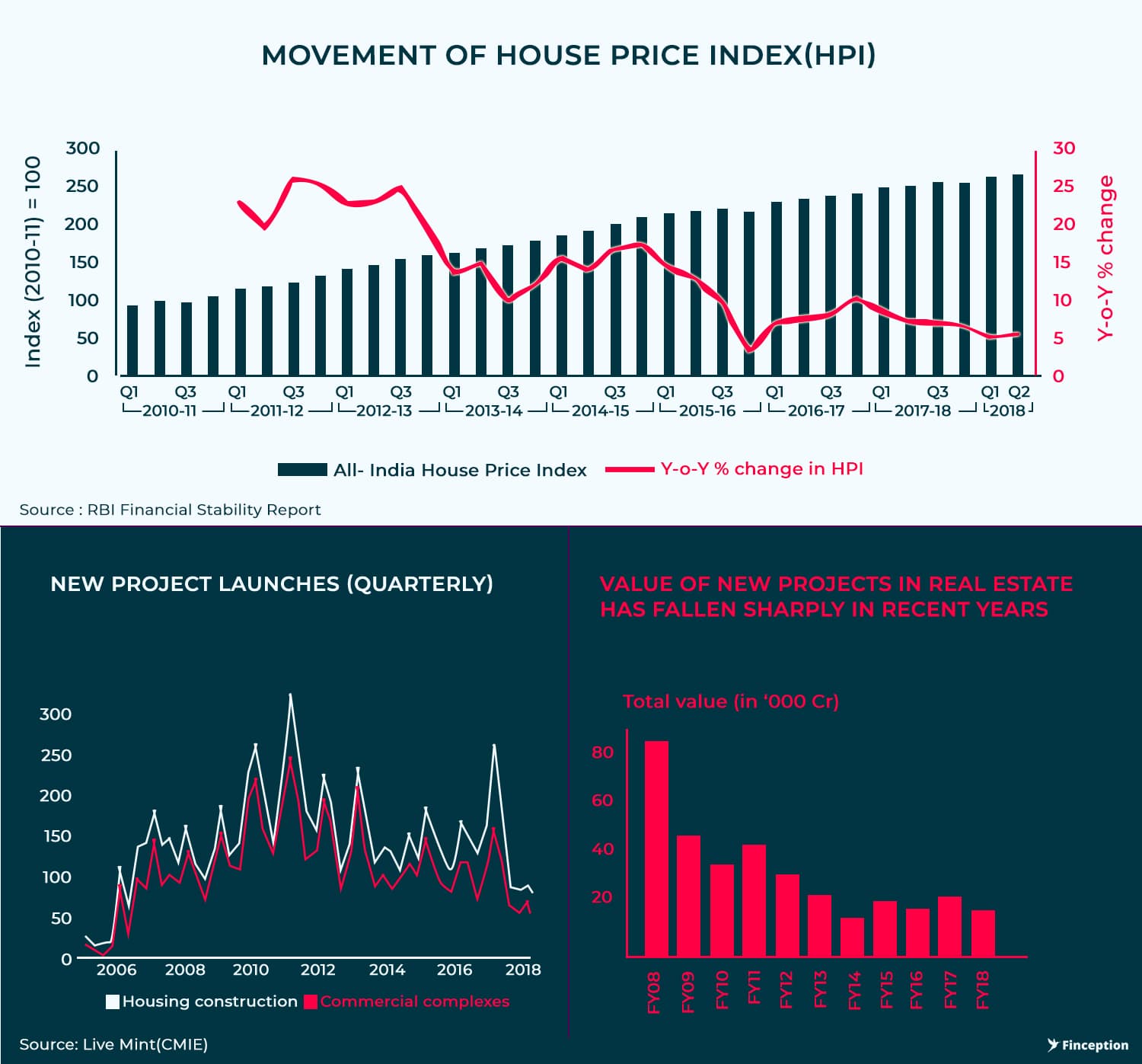

With interest rates creeping up, accompanied by a national wave of second thoughts about big purchases, we should have seen a correction in prices and an eventual downturn in the Real Estate sector. However, that did not happen. Instead, in a bid to shore up their bottom line, Real Estate developers resorted to negate the higher financing cost by selling houses at even higher prices. When prices are being driven up by credit-fueled property developers there is good reason for investors to exercise caution. Also, ironically this increase in property price also drove up the value of the developers' inventory, thereby providing room for even more debt. While in the short term this might benefit both lenders and developers. Over a longer time horizon, this artificial price inflation creates more problems than it solves.

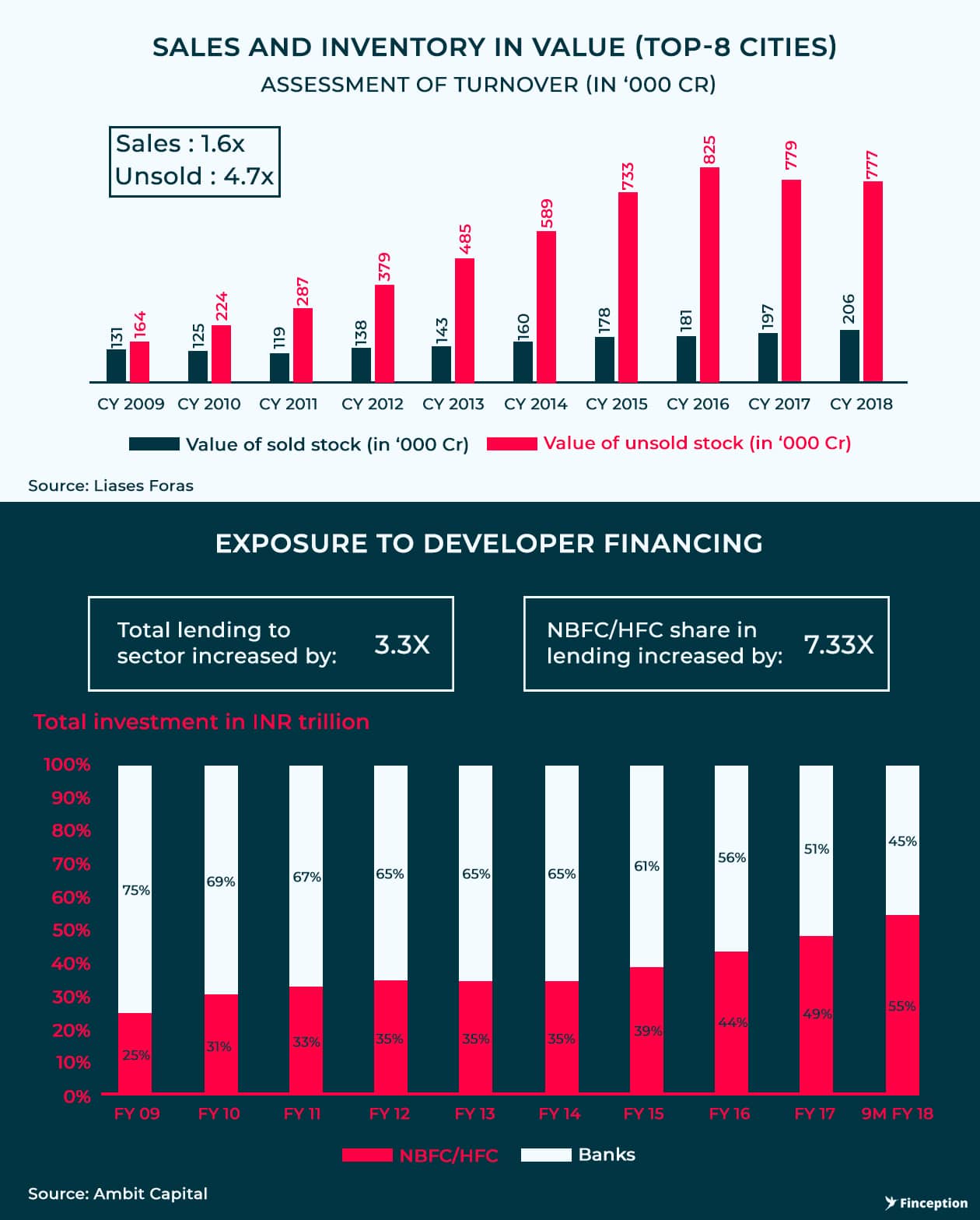

Firstly, by pricing out the middle-income consumer, developers inevitably end up hoarding a lot of unsold inventory stuck at various stages of development. Between 2009 and 2014, unsold inventory had more than doubled. You can't expect a middle-income consumer to fork over 1 Crore for a 2 BHK property. Secondly, as housing prices increase, rental yields on properties tumble. Rental Yield i.e. rent measured as a proportion of the total property value stood at about 6% back in 2008 and then declined to a low of about 2% in 2015 — meaning you could earn about 2% every year for the investment you make (outside of property price appreciation). This isn't a worthwhile money-making opportunity when you are expected to pay close to 10% in home loan interest. If prices don't appreciate disproportionately you could end up losing a lot of money. Even if one were to assume that home ownership is a cultural phenomenon and only a symbolic investment endeavour, property prices can't keep appreciating forever.

The increase is measured over a period of 10 years between 2009 and 2018

This is evidenced by the Spanish Housing Crisis that left the entire economy crippled. Between 2004 and 2007, when the bubble reached its peak, unsold new housing stock nearly quadrupled because of the excess supply over demand for replacement housing, tourism sector and even above speculative demand. This was also driven by disproportionate credit expansion (cheap debt) facilitated by local governments and further aided by property developers willing to take on large housing projects without assessing demand. The Spanish real estate sector showed signs that things could be changing but companies continued to be very aggressive so long as prices kept going up. When in 2008, the Global Financial Crisis started wreaking havoc, housing prices declined and almost 40% of all loans to the construction and real estate sectors became non-performing.

By the time the NDA government roared back to power at the centre, Real Estate developers were already in a spot of bother, although it did not show. Then, the government introduced a slew of stringent regulations against black money and revoked subsidies accorded to the sector during the UPA 2 era. Eventually, some developers began to show stress. The prudent measure then would have been to force defaulters to pay up or liquidate their assets. In the event that this strategy proved unviable, banks could initiate bankruptcy proceedings against these companies. However, this would mean that banks would have had to show these assets as non-performing — a big no-no in banking circles. So the banks and the companies that borrowed from these institutions found a rather convenient workaround.

As a chapter in the Economic Survey 2016–17 succinctly notes — "The strategy was, … to "give time to time", meaning to allow time for the corporate wounds to heal. That is, companies sought financial accommodation from their creditors (banks), asking for principal payments to be postponed, on the grounds that if the projects were given sufficient time they would eventually prove viable." It is also common knowledge that many Public Sector Banks were also engaged in 'evergreening' loans by extending more bad loans in order to fund their interest burden and cost escalation arising out of delayed completion. This pernicious cycle persisted until the RBI forced the banks to clean up their books during the Asset Quality Review (2016). And finally, the first casualties were reported. They came from the power and the Infra Sector. Strangely, Real Estate once again relatively escaped unharmed.

So why did the Infra companies succumb to this pressure when Real Estate companies emerged unscathed?

Banks normally lend against collateral including project assets. Unfortunately, Infra companies were involved in the construction of roads and airports — assets that can't exactly be mortgaged/sold. The only recourse available to these distressed companies in most cases was a termination payment in the event that the project failed to take off. The lenders also evaluated the creditworthiness of potential Infra companies primarily on the strength of future revenue streams. So when cost overruns and regulatory hurdles exposed weakness in the sector, banks cut lending. While the value of collateral for Real Estate companies were being revised upwards, revenue forecasts of Infra companies were being revised downwards.

"We are seeing a broad-based real estate pullback, with prices correcting in most tier-1 and tier-2 cities alongside sharp drops in transaction and new launch volumes. The drivers for this slowdown are a mix of supply-side factors (banks have pulled back lending to developers) and demand-side factors (the Black Money Bill has created fear amongst speculators) "— Ambit Research on July 14, 2015

By 2015, Ambit Capital one of India's best brokerage house/corporate finance firm had elaborated in great detail why they believed there was going to be a slowdown in the Real Estate sector. The rationale was clear — prices had already moderated given that commercial lending to residential real estate was drying up and developers were scurrying to sell off their unsold inventory at throwaway prices. This, they believed would finally bring about the price correction that was long overdue. In the event that they did not sell their inventory at reduced prices, they would risk default, especially the developers who had borrowed extensively during the credit boom.

Let's consider for a moment that this was how history panned out post-2015. If developers were in fact forced to sell off their assets at cheap prices to repay their debt obligations, housing prices would see a steep (and quick) decline. But when property prices drop, developers have to revalue all of their assets, even the unsold ones. This severely limits their ability to take on new loans for new investments (because their assets are now worth less than they used to be). Such forced deleveraging (reducing debt burden) could oblige developers to sell off even more assets resulting in a downward spiral of deleveraging and falling asset prices. In most cases, developers will simply throw up their hands and the burden will be borne by banks that resorted to cavalier lending without adequately assessing risk. The bottom line — NPAs start to show up as they did in the Public Sector Banks post the Infrastructure debacle.

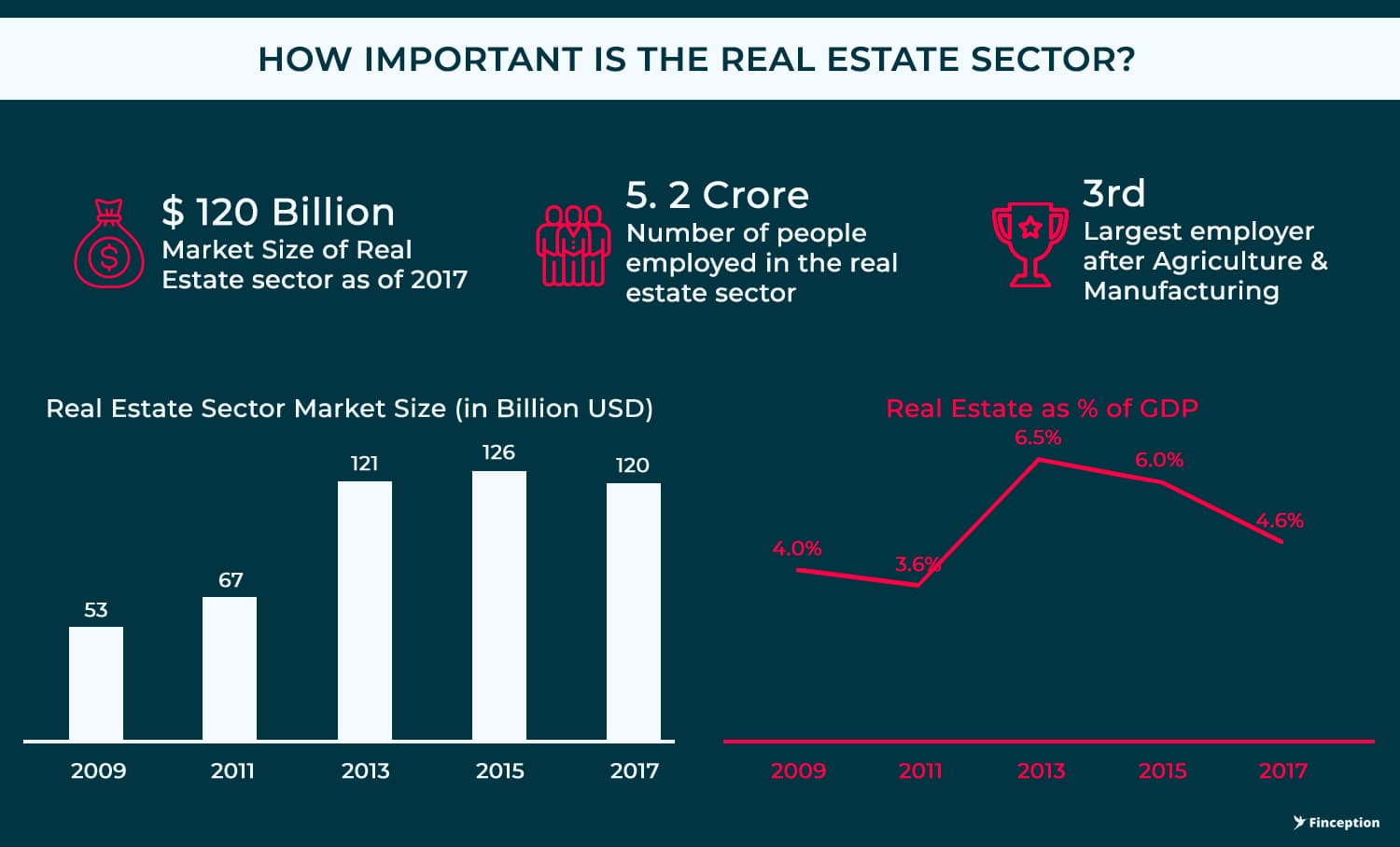

But despite Ambit's excellent prognosis, history did not quite pan out this way. Instead, as banks became wary of lending to Real Estate, private equity and NBFCs stepped in to fill the void. NBFCs share of the total lending pie towards developer financing more than doubled in 10 years since 2009 (from 25% to 55%). Outside of a few bankruptcies in the Real Estate Sector, by and large, there was still no widespread panic or a decline in housing prices (except Delhi) as evidenced by the Housing Price Index which continued to trudge along. But that doesn't mean all was well within the sector. When The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 was passed into law by the parliament, the pro-consumer legislation crippled developers. The provisions of the act severely restricted developers' ability to raise cash from prospective buyers and penalised them for late delivery of homes. Although property prices still stood firm, land prices came under pressure because demand from the Real Estate sector was almost non-existent. Then demonetisation hit the market, then GST and we had an industry almost at its knees begging for some respite. In predictable fashion, sales stagnated, margins kept eroding and the total debt continued to rise. Between 2009 and 2018 sales increases by 1.5x while debt moved up 3.3x.

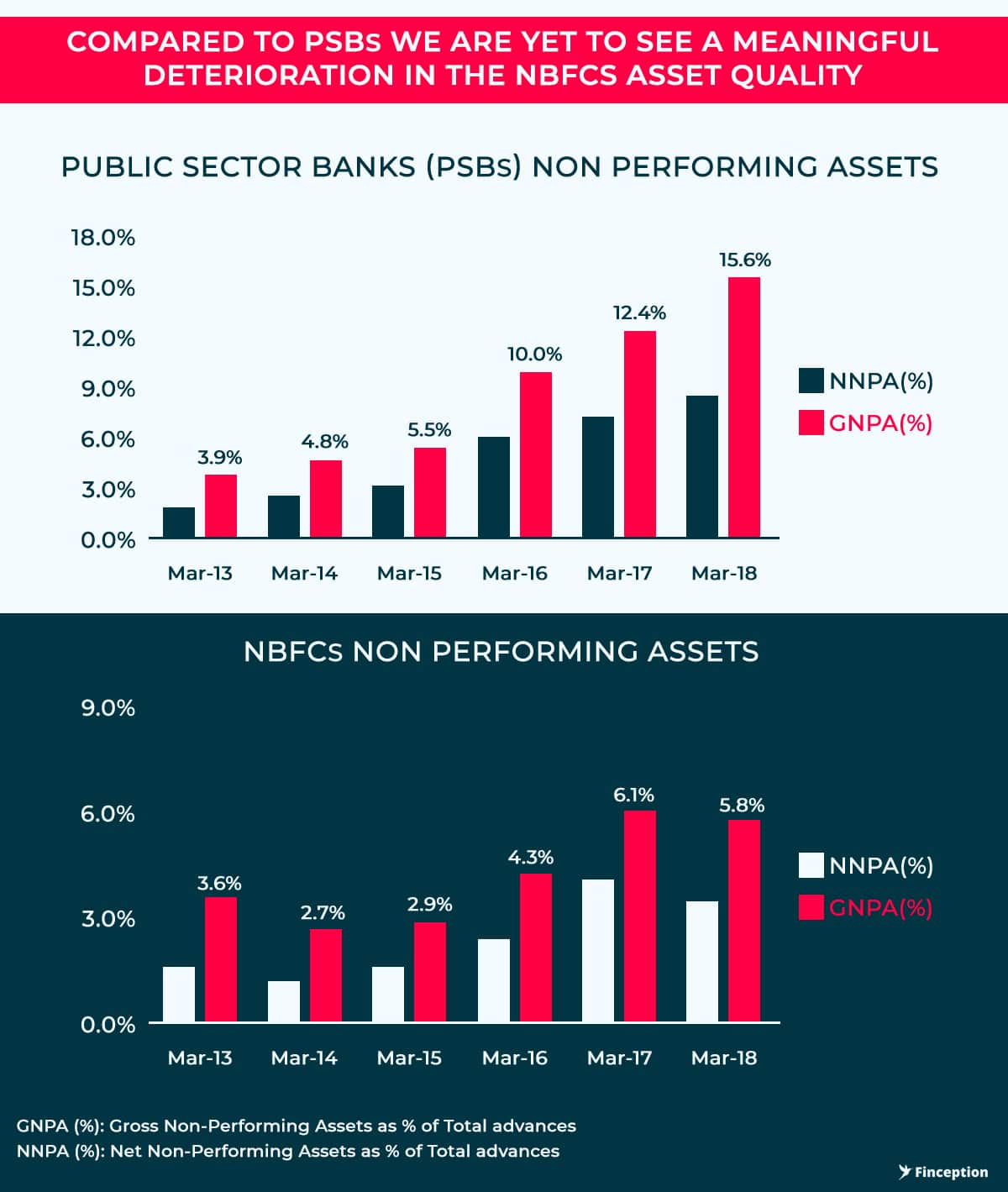

Yet, the lenders, especially the NBFCs had very little to show for all the stress in the Real Estate market. Their books were still good. But how?

While the public sector banks were mostly financing projects involved in the late stages of their development cycle, NBFCs were doling out loans to construction projects that had barely taken off. These were high-risk projects and the persisting stress in the Real Estate markets should have resulted in a spike in NPAs, more than what was being reported. However, as we have already noted this wasn't the case. It seemed as if NBFCs had taken a leaf out of Public Sector Banks and were also evergreening/refinancing loans. In another excellent report, Ambit details the accounts of several NBFCs that are engaging in daredevilry or in other words "risky developer financing". The report carefully lays out a detailed explanation of how NBFCs have been getting around the whole NPA quagmire by being slick. The likes of Piramal and JM Financial are particularly vulnerable because of their high exposure to developer loans, stressed cities (where RE is under duress) and significant Asset Liability Mismatches. We would have loved to run our own assessment on NBFCs if we had all the data. Unfortunately, we are too poor to buy/access primary data that might help us better understand the scale and magnitude of the crisis. So you will have to read the Ambit report if you want to know more about the risk profile of various NBFCs.

However, despite the obvious troubles, there are enough optimists out there thinking that the Real Estate sector is on the brink of a turnaround. Well, they do have a point. The cynics have been dissing Real Estate since 2014 now and we are yet to see any meaningful deterioration in prices. Another contention is that despite the festering problems of NPAs stoked by the Infrastructure and the Power sector, at no point, did we even come close to a full-blown crisis. There was no real fear of banks closing down or an immediate need for liquidity support or even street talk of large scale intervention. Also, there is all this talk of Affordable housing and the need to house millions who are still looking for quality shelter. Surely that will spur demand? Why should we fear this time around?

Well because we think this time it's different. During the Infrastructure IC1 debacle, most of the problem was concentrated in the Public Sector Banks — banks that are ultimately backed by the Sovereign (Government). The implicit guarantee accruing out of this relationship staved off panic, helped restore market confidence and lending resumed as usual (except for some minor blips). So even if they did engage in evergreening loans and reported large NPAs, they would still wiggle out of a crisis relatively unscathed. But when NBFCs try to sweep the problem under the rug, they are tempting fate because there is no sovereign backing. Most of these players have been issuing long term loans by borrowing over ridiculously short time frames and "rolling them over" once they mature. In banking parlance, they call this running an Asset Liability mismatch (ALM) — a grave offence during testing times. (To know more about ALM and other banking jargons read our story on the NBFC Financial Crisis).

In the event that NBFCs find it difficult to raise funds — and they are finding it difficult to raise money post the IL&FS crisis, the refinancing/evergreening malaise will have to unravel. Real Estate developers will have no place to go except sell all their inventory at throwaway prices. We already saw how that ends and it's not pretty. The last recourse for the optimist is the 'affordable homes narrative". Even if one were to assume that affordable homes will, in fact, hit the market and help reduce stress we must evaluate the effect of these new low price homes on the existing unsold inventory that's grossly overpriced. What happens to all the expensive stock? The obvious answer is that Real Estate developer will have to revalue this inventory and we will see the development unfold through NPAs and price declines(residential). This is what Pankaj Kapoor, the MD of Laises Foras was hinting at when he said — " It feels that the situation of developers is akin to an elephant in a well which is unable to come out on its own. Somebody needs to replenish the well. But can we find cheap capital to refill the well?". In the current environment (post-IL&FS crisis) there's nobody to turn to for additional capital. They can't increase sales, cant push margins, can't refinance loans. So how will the developers come good on their interest payments?

Readers must note that the big developers are frantically trying to reduce their debt burden by selling stake in their company. DLF has been trying to raise over 4000 Crores for over a year to pay off debt (Unsuccessful because of unfavourable market condition, it notes). Other companies have been trying to sell off their non-core assets to deleverage. The government is considering to ask NBCC to take over several unfinished projects in a bid to complete them (stalled projects post bankruptcy or funding troubles). There is also talks of GST relief for Real Estate Sector. However we believe that before the Real Estate Sector turns around there will be more pain — housing prices will decline and more NPAs will show.

. . .

Enjoyed reading? Show us your love by sharing...

Tweet this articleReview & Analysis by Pawan, IIM Ahmedabad

Liked what you just read? Get all our articles delivered straight to you.

Subscribe to our alertsDisclaimer: No content on this website should be construed to be investment advice. You should consult a qualified financial advisor prior to making any actual investment or trading decisions. The author accepts no liability for any actual investments based on this article.

READ NEXT

Get our latest content delivered straight to your inbox or WhatsApp or Telegram!

Subscribe to our alerts